The Three Most Chilling Conclusions From the Climate Report

Thirteen federal agencies agree: Climate change has already wreaked havoc on the United States, and the worst is likely yet to come.

On Friday afternoon, the U.S. government published a major and ominous climate report. Despite being released on a holiday, when it seemed the smallest number of people would be paying attention, the latest installment of the National Climate Assessment is, as told to my colleague Robinson Meyer, full of “information that every human needs.”

The report traces the effects climate change has already wrought upon every region of the United States, from nationwide heat waves to dwindling snowpacks in the West. In blunt and disturbing terms, it also envisions the devastation yet to come.

The document’s dire claims, backed by 13 federal agencies, come frequently into conflict with the aims of the administration that released it. Where the Trump administration has sought to loosen restrictions on car emissions, the report warns that vehicles are contributing to unhealthy ozone levels that affect nearly a third of Americans. Whereas the president has ensured that the United States will no longer meet the goals outlined in the Paris Agreement on climate change, the report says that ignoring Paris could accelerate coral bleaching in Hawaii by more than a decade.

Here are the report’s three most chilling conclusions:

1. Extreme hot weather is getting more common, and cold weather more rare.

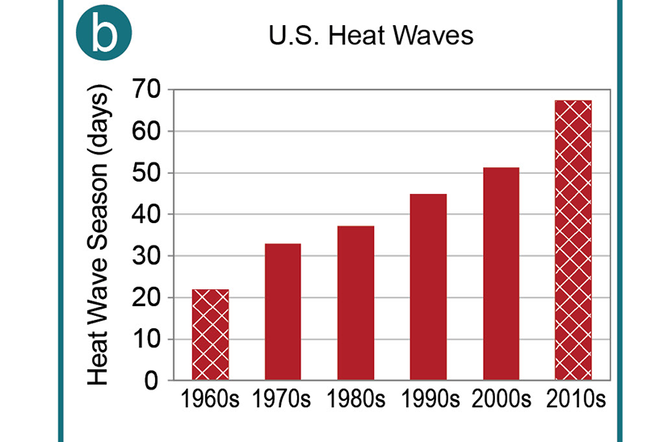

In its first chapter, the National Climate Assessment reports that heat-wave season has expanded by more than 40 days since the 1960s. In the bleakest scenario of unchecked climate change, Phoenix could have as many as 150 days per year above 100 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century.

Over the past two decades, the number of high temperature records recorded in the United States far exceeds the number of low temperature records. The length of the frost-free season, from the last freeze in spring to the first freeze of autumn, has increased for all regions since the early 1900s. The frequency of cold waves has decreased since the early 1900s, and the frequency of heat waves has increased since the mid-1960s. Over timescales shorter than a decade, the 1930s Dust Bowl remains the peak period for extreme heat in the United States for a variety of reasons, including exceptionally dry springs coupled with poor land management practices during that era.

Over the next few decades, annual average temperature over the contiguous United States is projected to increase by about 2.2°F (1.2°C) relative to 1986–2015, regardless of future scenario. As a result, recent record-setting hot years are projected to become common in the near future for the United States. Much larger increases are projected by late century: 2.3°–6.7°F (1.3°–3.7°C) under a lower scenario … and 5.4°–11.0°F (3.0°–6.1°C) under a higher scenario … relative to 1986–2015.

Extreme high temperatures are projected to increase even more than average temperatures. Cold waves are projected to become less intense and heat waves more intense. The number of days below freezing is projected to decline, while the number of days above 90°F is projected to rise.

2. Climate change has doubled the devastation from wildfires in the Southwest.

According to the report, human-caused climate change has heated and dried out the American Southwest, leading to deaths, enormous costs, and lingering health consequences.

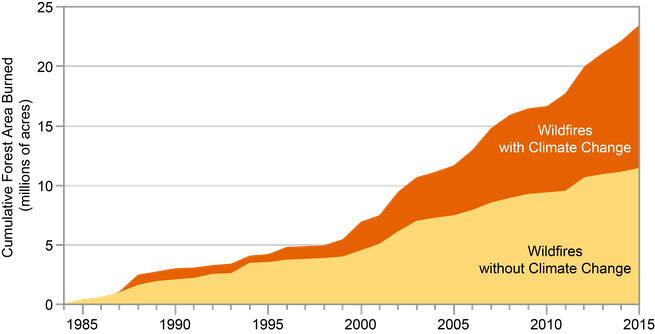

Climate change has led to an increase in the area burned by wildfire in the western United States. Analyses estimate that the area burned by wildfire from 1984 to 2015 was twice what would have burned had climate change not occurred. Furthermore, the area burned from 1916 to 2003 was more closely related to climate factors than to fire suppression, local fire management, or other non-climate factors.

Climate change has driven the wildfire increase, particularly by drying forests and making them more susceptible to burning. Specifically, increased temperatures have intensified drought in California, contributed to drought in the Colorado River Basin, reduced snowpack, and caused spring-like temperatures to occur earlier in the year. In addition, historical fire suppression policies have caused unnatural accumulations of understory trees and coarse woody debris in many lower-elevation forest types, fueling more intense and extensive wildfires.

Wildfire can threaten people and homes, particularly as building expands in fire-prone areas. Wildfires around Los Angeles from 1990 to 2009 caused $3.1 billion in damages (unadjusted for inflation). Respiratory illnesses and life disruptions from the Station Fire north of Los Angeles in 2009 cost an estimated $84 per person per day (in 2009 dollars). In addition, wildfires degraded drinking water upstream of Albuquerque with sediment, acidity, and nitrates and in Fort Collins, Colorado, with sediment and precursors of cancer-causing trihalomethane, necessitating a multi-month switch to alternative municipal water supplies.

3. Rising sea levels will necessitate mass migrations, and coastal cities aren’t doing enough.

The report’s chapter on the coastal effects of climate change warns that sea-level rise alone could force tens of millions of people to move from their homes within the next century.

Shoreline counties hold 49.4 million housing units, while homes and businesses worth at least $1.4 trillion sit within about 1/8th mile of the coast. Flooding from rising sea levels and storms is likely to destroy, or make unsuitable for use, billions of dollars of property by the middle of this century, with the Atlantic and Gulf coasts facing greater-than-average risk compared to other regions of the country …

Climate change impacts are expected to drive human migration from coastal locations, but exactly how remains uncertain. As demonstrated by the migration of affected individuals in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, impacts from storms can disperse refugees from coastal areas to all 50 states, with economic and social costs felt across the country. Sea level rise might reshape the U.S. population distribution, with 13.1 million people potentially at risk of needing to migrate due to a [sea-level rise] of 6 feet … by the year 2100. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe on Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana was awarded $48 million from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to implement a resettlement plan. The tribe is one of the few communities to qualify for federal funding to move en masse …

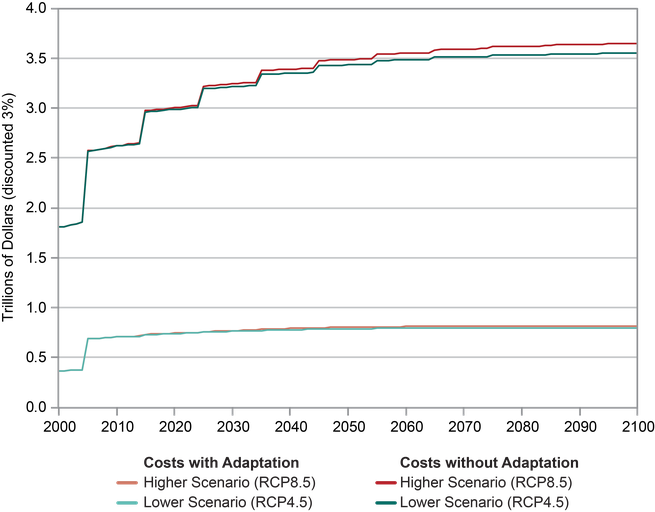

It remains difficult … to tally the extent of adaptation implementation in the United States because there are no common reporting systems, and many actions that reduce climate risk are not labeled as climate adaptation. Enough is known, however, to conclude that adaptation implementation is not uniform nor yet common across the United States … The scale of adaptation implementation for some effects and locations seems incommensurate with the projected scale of climate threats.

Robinson Meyer contributed reporting to this article.